01.10.20 embarking

This week I celebrated the 37th anniversary of my terminal cancer diagnosis in the usual way – by embarking on an improbable secret project. For the next year or so I won’t have time to update this journal, so I leave you with some thoughts about the past and the future:

Last summer I was walking through downtown Seattle staring at all the shiny new skyscrapers and thinking about the city in the 80’s, when it was dirty and semi-derelict and a lot more fun, with all-ages venues and record stores and KJET.

Eventually I ended up on the new viewing platform at Pike Place Market, built adjacent to the remains of the Alaskan Way Viaduct. I stood there for awhile, snapping photos of the dismantled highway.

I’ve driven most of SR 99 from Canada through California, and prefer it to the modern anonymous streamlined I5; I’m a backroads kind of person. But this part, the elevated platform of the Pacific Highway, always frightened me. When driving I would do anything to avoid it, including taking long circuitous routes through the city. Whenever I was a passenger I kept my eyes firmly closed. Hurtling through a narrow concrete channel in the sky, with a three foot high barrier on each side, I was convinced I would die.

However, I will miss the Viaduct – or at least the view of the Viaduct as seen from the decks of the ferries traversing the bay. The city I remember from childhood has been thoroughly dismantled. The Space Needle is the only recognizable part of the skyline left.

Eventually I realized the stranger next to me was talking to other strangers, jovially telling tall tales about the city. I wanted to intervene, to correct his assertions not just about the Pacific Highway, but also about the name of the waterways, the history of settlement, and most importantly, the body of land shrouded in mist across the water. But I resisted. I am genuinely a local, and that means (amongst many other learned behaviors) I never talk to strangers.

What did I feel, staring at the peninsula and islands in the distance? Certainly a profound sense of loss over my mother, aunt, cousin, and all the others who have died. Without question a muddled longing to remain here, on the water, between the mountains. I only know north and south when I can see the peaks of the Olympics. No other landscape makes sense to me: I live elsewhere, but this will always be home.

Staring at the shattered edge of the old highway, it struck me that it has been thirty years since I finished high school. Logically that meant that there must have been a reunion. I still have friends in town but nobody mentioned it, and since I never look at social media I would not have seen a group invitation or any of the preparations.

Immediately after this crossed my mind I felt a sense of relief – the decision was out of my hands! How funny, and how modern: technology thwarting social cohesion. I turned around and started walking back up toward Capitol Hill, idly noting streets and buildings that were meaningful destinations in my teen years.

As I walked toward the Paramount I reviewed the reasons people say they go to reunions, made a list of movies on the subject, and cross-referenced the data with my own undefined feelings. Was I curious about how life turned out for everyone? Kind of. Do I hold a grudge against anyone? Not really. Do I want to make my historic enemies feel small? No. Do I need validation of my life choices? Never.

Adolescence could have been a nightmare: I was sick, intermittently homeless, my family was chaotic. But the cancer had slowed down. My hair was growing back, I could walk and talk and see and breathe. For awhile each moment felt like a miraculous gift, far too precious to waste on sad thoughts. Who cares about cliches, I was thrilled to be alive: first car, first kiss, freedom!

My yearbooks are in a storage unit in London. I looked at them a few years ago, reading comments from teachers who (before I dropped out in the eighth grade) used words like “perseverance” and “fortitude” to describe me. Some of my peers left comments like “don’t die” and “stay alive” – with exclamation points and doodles.

I had no desire be inspirational, because that is an insipid and insidious goal. And it was obvious I would never be normal. But I wanted to have fun, and do hard work, and accumulate experience. There is a distinct shift when I went back for high school: close friends ignored the drama and penned long, cryptic messages about our adventures. Many never knew I was sick – by the start of sophomore year it was possible to hide the scars.

I woke up every morning with a missionary zeal to entertain and educate myself, and those around me, whether they liked it or not. I took every class and subject I could cram in my schedule, and volunteered the rest of my time – tutoring younger kids, working at a veteran’s home, shepherding the foreign exchange students. I published zines, went to leadership camp, competed in regional Vocational Industrial Clubs of America contests. I instigated frivolous jaunts like dog weddings, rotating group dates, button wearing contests. I dressed my pals in sheets and staged Julius Caesar in the barbecue shelter at Manchester State Park.

The car accident destroyed my good mood, but not my inherent character. In the midst of the trauma I didn’t know what to do except stay busy. I ran a renegade health education clinic out of my locker, and started a statewide nonprofit.

My teenage self was organized: I had a clipboard and a plan. I was, according to the reviews in the annuals, “quirky” and “relentless.” Several people offered me money to go away. If anyone called me a bitch I flipped to a tally page in my notebook (33 instances over three years) and interrogated which of my specific personality traits generated the slur, with pie charts to illustrate possible options. In other words: I was buoyant, divisive, and deeply annoying.

When I look back the facts that stand out above all others are the manifestations of economic indicators. I grew up in low income housing projects, with all the attendant dangers. Adding the material risks of rural life does not improve the statistical outcomes. How did that turn out for everyone? About as well as you might expect.

It is significant that there was no particular income disparity in the student population. We lived in a working class place, with lower middle class trimmings bought on layaway. The only rich kids in the area lived on an island in the north end of the county. They had their own facilities, and we did not mix. I genuinely had no idea I was poor until college, where I felt stranded and uncouth without quite knowing why.

The kids who grew up in nice families have lives that correspond to those traits, regardless of any other factor. Those who suffered abuse have struggled. The daredevils and pranksters and miscellaneous rascals who bedeviled the lives of the unwary have conformed to type. Friends, enemies, exes: have there been any surprises? No.

Our high school was large, impersonal, but adequate. The building was new, the sports teams were well funded, the vocational courses abundant. Academic programs were small and hard to access, but it isn’t clear if that was administrative bias or a population preference. Was it an imperfect system, prone to failure? Yes. But that is pretty much how life works.

Continuing the walk up the hill, past the storefront that used to be the Bauhaus cafe, I was surprised to find that I had even a flicker of interest in the reunion. One key problem is the simple fact that these events cater only to a specific graduating class. The school I attended was bigger than the population of the town, because kids were bussed in from the entire southern half of the peninsula. And I didn’t live in town – I lived on the furthest unincorporated edge of the county. Yes, I had a few friends from the Class of ’89, but most of my close companions were from different grades, other parts of the peninsula, elsewhere in the state, or military families, just passing through.

If only 20% of the average class goes to any reunion (which seems like a reasonable guess), how many of those would I remember? And on a practical level: if I only know someone because we were alphabetically assigned adjacent seats thirty or forty years ago, what would we discuss? I’m not good at small talk, it makes me queasy to answer questions.

Where do I live? Here and there. What is my job? Oh, well, you know. This and that. How’s my mother? Dead. Next topic. Do I have kids? Yep. What are they up to these days? Um. Yeah. Fancy stuff. Mumble, mumble, how about we change the subject.

But there are a few people I lost track of and still wonder about, like the funny tall gregarious girl who became my best friend on the first day of kindergarten. Growing up we danced to ABBA on my Disco Sound Machine, ran through the woods screaming Joan Jett anthems, shared secrets, snuck out to concerts and movies she wasn’t allowed to see.

That friendship lasted through all manner of adversity and change. She was with me, holding my hand, as my daughter was born. But despite all that – or maybe because of it – she vanished from my life. I wonder how she is, where she is, but I respect her decision to disappear. It was her choice to make, and I don’t need to know the reason. We were children. People grow up.

If I wanted a metaphor to explain how I feel about high school, the Alaskan Way Viaduct would be ideal. The elevated roadway was intended to be a permanent structure, but an earthquake changed everything. It took years and a massive investment of money to figure out the best way to replace the infrastructure. The elevated concrete platform was demolished, ending an era, changing the city. But the destruction of the highway created a clear view across the bay.

The intervening decades have illustrated that my teenage life was defined by a pragmatic urge toward safety. I was motivated by the need to obtain an education, feed my child, avoid anyone who threatened to harm us. I was trying to predict and prevent dangers that were manifestly real because I was a poor sick kid in a small town. I was trying to survive, and I knew that I had to save myself.

Everything in my past – good, bad, or indifferent – contributed to the life I have today. I’m not ashamed of where I come from, and I’m not proud of where I landed. I’m alive, and that is sufficient.

I don’t blame the Alaskan Way Viaduct for the terror I felt while driving: it was just a road. Similarly, the high school I attended deserves neither castigation nor credit for the excesses of my teen years. Both the road and the school were shaky, perilous, but ultimately adequate structures to get from one place to the next.

My life has taken me down different roads, to faraway destinations I could not have imagined as a child. The choices I have now would not make sense to that impoverished little girl. The opportunities I am contemplating would baffle the ambitious teen mom who packed up her baby and ventured out into the world to acquire an education.

The career I’ve built would astound the young woman driving over two hundred miles every day with a rambunctious toddler in the backseat because the only way to survive involved making a constant circuit between the army base, the college campus, and the cancer clinic.

No version of me expected to be alive at age 49. It is strange and amazing that I managed to write and publish books, start nonprofits, run companies, move to other countries, meet and befriend thousands of people, watch my children grow to adulthood. The critical point is that I was always willing to begin the journey: get in the car, get on the plane, start something, do anything, say yes.

I didn’t believe I had a future, so I went out and made my own. The most important lesson though? The real and shocking truth? Even in the worst of it, I have always thought my life was a grand and hilarious adventure. From the shores of Puget Sound to the banks of the Thames and beyond, this life has been endlessly entertaining. Everything else is incidental.

I hope that everyone I knew growing up arrived where they were headed, and that they have been satisfied with the journey. But for me, the old road is closed.

12.15.19 bias

Recently I was at a formal wedding reception in a private club. Nobody in the room was circulating, we were all seated according to a strict plan, listening to speeches. In the gap between toasts a man walked up to our table and started talking very intensely to my husband, who listened politely, but with a bemused expression. It was not the moment to mingle.

After a minute it became clear that the fellow looming over us was an angel investor. Someone had pointed toward our table and told him that he should meet the startup CEO who sold their last company to Facebook. Mr. Investor raced over, wasting not one second on small details like the identity of the CEO.

Surveying the table of twenty people, he had decided on instinct that the tall guy with Joe 90 spectacles was the target. His pitch was swift and succinct, he hit all the relevant points, and was in the middle of the traditional exchange of business cards before my husband could say anything. When he could get in a word, aforementioned husband (who, while exceptionally talented, does not have the stomach for startups) pointed at me and said “Uh yeah… I think you want to talk to her.”

The man in the gray suit was visibly startled. The hand holding out the business card twitched, and he looked down at me, flummoxed. I raised my eyebrows and waited. He put his card back in his pocket, mumbled something inaudible, and walked away.

It was classic, like a low budget comedy from the 80’s, or a Rowan Atkinson cameo come to life. I turned to my husband and said “Did that just happen?” He shrugged, and we went back to watching the wedding speeches.

Another guest at the table overheard the exchange and sought me out later. He’s an executive at a major US company and was incensed over the implication that Mr. Investor dismissed me solely based on gender. I laughed, and said “I like it when people reveal bias. It is so much more… efficient.”

Perhaps the man reacted to my gender – there is no way to know. It could have been a hundred other cultural markers, or none at all. I’m not especially sensitive to this kind of thing: I worked my way out of poverty through hard graft. There are very few insults I have not endured, and there isn’t much in the way of human behavior that surprises me. Some of the injuries I’ve sustained along the way were intentional, but most were inadvertent.

Everyone grapples with the chaos of their own lives. It is easy to make mistakes, or get angry and lash out. Sure there are tricksters and provocateurs trying to cause trouble, but mostly people speak before thinking, which is excusable in almost every instance. I do it all the time, alienating people right and left with my strong opinions about sunblock and seatbelts and handwashing.

When a stranger contrives something as spectacular as Mr. Investor, I tend toward the charitable explanation. My first thought was that he must have been embarrassed over his mistake.

But he was definitely expecting something else. In the current startup climate, that is usually (regardless of gender) glad-handing self-promoters, people who want to tell you all about their great new idea, etc etc ad infinitum. If Mr. Investor was expecting a pitch he was definitely disappointed.

Perhaps he had a vision of what a tech CEO looks like and I didn’t match, but if so it could have been anything: gender, clothes, age, crooked teeth, backwoods accent.

Realistically, none of this matters. Humans make choices based on their own idiosyncratic interpretations, and there is opportunity cost in every outcome. Maybe the angel investor made a category error in walking away; maybe he guessed correctly that we would not get along. Who knows, and also – who cares? I enjoyed the exchange: it was hilarious.

09.01.19 slack

I am a difficult, prickly mother, heavy on pep talks and paperwork but light on emoting.

I’m also a firm believer that excellence is required at all times.

Did the kids get any slack when they were small, sad, ill, or adolescents? After a death, during a breakup, or because they were immigrants? No.

When I say they were not allowed to complain, I actually mean I couldn’t hear them if they tried. Moan or mope or whinge: I literally did not listen, not to a single word. Not when they were infants, and certainly not as they entered adulthood.

It is a wonder they talk to me at all.

I required civility, but never fealty. Discipline, but not deference. I raised them to be autonomous, knowing that meant they might reject everything about their upbringing. I boycotted my own family of origin; it would not have surprised me to be rejected by my adult children.

Yet here we are, on the other side. Everyone is old enough to make their own choices. I am surprised to find that they talk to me every day, no matter where they are in the world. They tell me funny stories, and laugh at mine. They ask for my advice on navigating bureaucracy, and ignore my advice on almost everything else.

Scheduling conflicts mean we’re rarely in the same place but when we are, we gravitate together, sitting as close as possible, chattering and mocking.

My youngest child just moved to London to start grad school at a conservatoire affiliated with the Royal Opera House. The cliche about time going by too fast really is true: one minute they’re babies, the next they are gone. They’re also exactly who they always were: this is the child who asked for musical instruments as soon as he could talk.

It has been an honor to know them and watch them grow.

08.28.19 transit

On the afternoon of the reunion I hadn’t decided whether I would go or not. But the event was scheduled to happen two hundred miles from where I was standing, so it seemed unlikely.

We wandered around our old neighborhood, contemplating once again the question of moving back to the NW. There is no consensus within the marital unit: opinions change with the seasons.

At almost the exact second I had to decide whether or not to head north I started getting texts from friends who had just learned I was in town. They informed me there was a birthday party for Marisa, and I should definitely cancel all other plans to attend.

When I rolled up to the party I found something quite unexpected: yes, the yard and house were teeming with strangers, but there were dozens of people I knew and loved including several I had not seen in seventeen years. I had wandered, accidentally and serendipitously, into a different kind of reunion.

The group of people sitting in Marisa’s yard are only loosely connected, we’ve scattered all over the world, meetings are erratic. But this is a basic truth: nobody asks me questions I cannot answer. Nobody cares about my job, or is puzzled by where I live. They do know my kids, but they don’t know my cousins. Or rather, a couple of them are probably my blood kin, but none of us would bother to figure out the details.

In fact, these people are perfectly happy to sit next to me without talking at all – and there are no awkward silences.

The people I befriended in my late 20’s have many things in common, but it isn’t easy to define why we’re friends. I suspect a key element is the fact that seventeen years can pass without comment.

We’re all doing what we want to do, whatever that is, wherever it is. I never know where I’ll see them, because we’re always in transit.

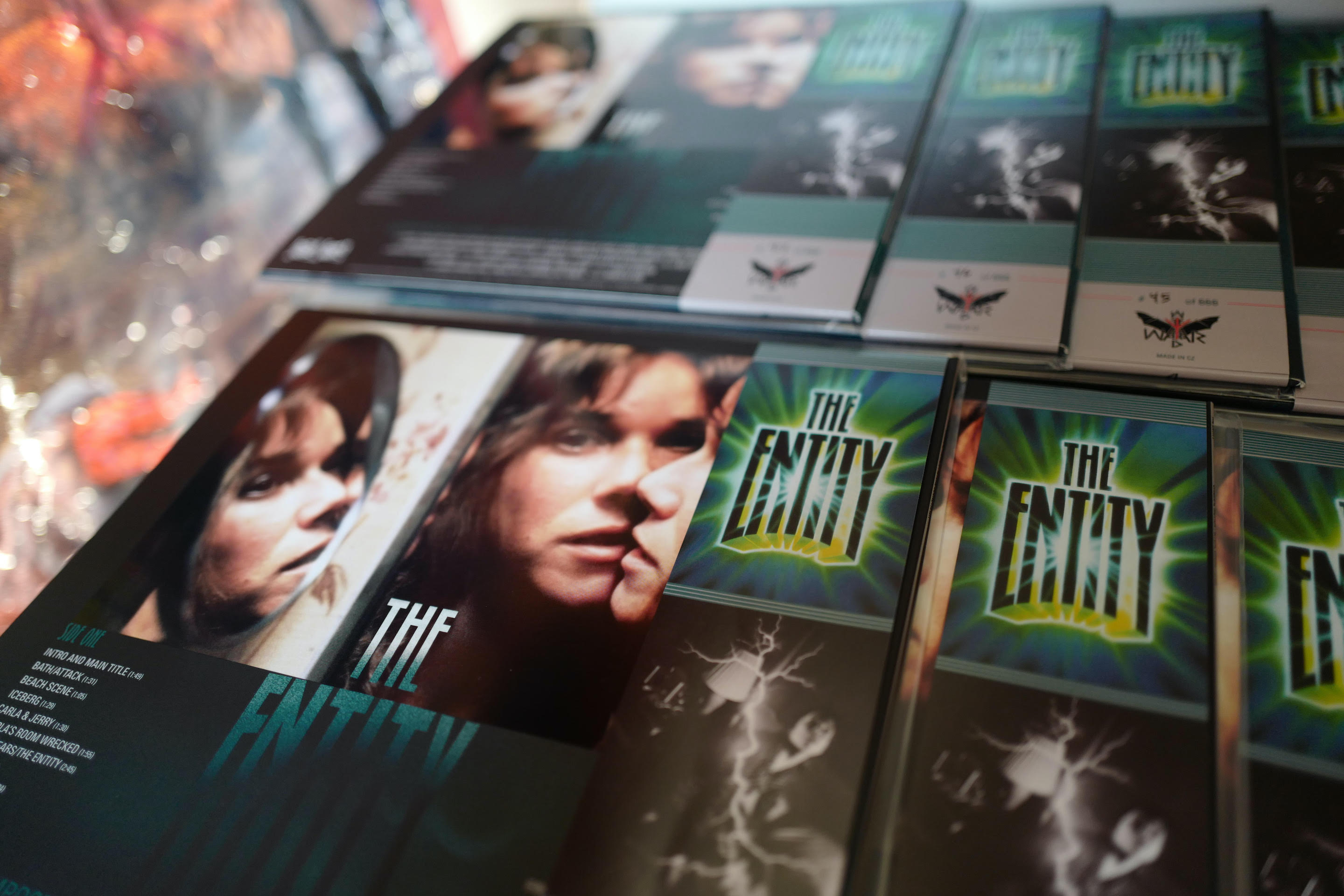

08.14.19 entity

With our good friends Dennis & Meadow at Wyrd War.

They’re releasing a special limited edition recording of The Entity soundtrack (first time on vinyl) – we got #666!

07.30.19 visceral

My son flew out to meet us in Seattle, his first visit as an adult. We walked around looking at all the things we both remember from our separate childhoods, and all the things that have changed.

The Pike Place Market is largely recognizable, and although I no longer know the people serving, the donut robot is still churning out little bits of fried deliciousness (enjoyed vicariously by celiac members of the family).

It is easy to spot a local, even in my small family. The kid who came of age in London jaywalks, while I stand obediently waiting for the light to change. We could hear passerby speaking in the regional accent (it annoys my son that I revert whenever I spend more than a few hours here) but it was like listening to ghosts.

I grew up on the Puget Sound and lived in the Pacific Northwest for the first 33 years of my life, my kid lived here until age six, but neither of us had a chance encounter with lost friends or misplaced blood relatives. Instead, he stumbled across people he met in college in rural Vermont, and I randomly encountered colleagues from London and New York.

This is the first time he’s been back since my mother died, and her loss changes how we experience the city. There is no longer any reason to ride the ferry out to the peninsula, no excuse to go to Randy’s, no binge of thrift stores and swap meets. We miss her all the time, but the feeling is more visceral in Seattle.

The city feels familiar but uncanny. It is eerie being in a place we know so well, after the people we loved best are gone.

07.20.19 paradise

David was in Manhattan a few weeks ago and we met for dinner. There was a lot to catch up on – we hadn’t met since his wedding – and it was, as always, delightful to see him.

We’ve both lost parents and talked about that for awhile. His mom was sweet, mine was entertaining, and they both died too soon for their lonely-only children. We discussed obituaries, and tributes, and grief. David went back for his mom’s service, but mine didn’t want a funeral. It was comforting to talk to someone from home, if surreal to sit in a Manhattan restaurant comparing hometown mortuaries.

Skipping across other topics, we compared notes on what the old crew is doing lately. Back then I only knew people who were seated alphabetically around me in classes: H-M was the limit of my social horizon. But David had friends (from Boy Scouts? Grade school? I never knew) with surnames that started with letters as esoteric as B and G, and the weirdest amongst us coalesced into a social group. Our collective teen years revolved around classic pretentious youthful venues: the art room, the drama department, band, international club.

We had lockers in the same hallway by happenstance, and then by choice. We shared rides, gossip, mix tapes. Our little crew encompassed miscreants but most of our misadventures were pranks – forking lawns, moving effigies between stands of trees, trick or treating and egg hunts out of season. We adopted exchange students and dragged them along, often against their will. We threw candlelit dinner parties in supermarket parking lots, and skipped school to take the ferry to Seattle to go to matinee performances of Shakespeare plays.

I’m neither sentimental nor nostalgic but it was good to laugh with someone who knew the version of me sporting despised pink spectacles and a JC Penney perm chosen by my mother. When we met, David had no idea that I was in the middle of cancer treatments, and I still don’t know what secrets he was harboring. But there is huge value in talking to someone who was there, who knew the same people, walked on the same beige carpets, suffered through the same pep rallies.

We talked and laughed for hours before he said something casual about the summer he worked on Mt. Rainier. I smiled and shrugged, then watched as the emotions raced across his expressive face. Counted one, two, three, and there it was: the flinch as he remembered what happened the day I drove up to visit him in Paradise.

This is the inevitable part of any visit with friends from home. Eventually, inexorably, no matter how well intentioned, they remember, and the memory hurts. Not just the fact of the accident, but the aftermath. Four lives destroyed. Five years of lawsuits. Injury, devastation, violence, chaos.

I can recite the facts, because I was the only witness and my testimony was required. But I’ve never discussed that day with anyone who was there, or the kids who were supposed to be there, or the people we visited on the mountain. What could I possibly offer? They’re lucky they don’t know, can’t remember. I wish I could forget, but thirty-one years later I still have a box of photographs, transcripts, hospital bracelets, blood soaked clothes cut off broken bodies in a ditch in rural Washington.

The accident isn’t a suitable topic for any social occasion. I steered the conversation toward safer subjects: how much we miss the mountains and the water, how the place that made us lives in our bones.

07.15.19 indicators

My house is always full of guests, but only a few have noticed that I have a new project. Stella and Al figured out I was up to something, but during a recent stay managed to wrangle just a scattered few sentences on the subject. Sara clocked that I was taking phone calls (aberrant behavior – I literally never use the phone except in my business life) and enquired; compelled to tell the truth I admitted I was hiring, you know, employees. Engineers, to be specific.

Why? Because I started a new tech company last year, and most of my thoughts and actions have been caught up with the whole thing, which I would never talk about at the dinner table or in mixed social groups. I discuss it with colleagues, attorneys, accountants, and customers; in other words, the people who are involved with the project. But I don’t see the point of chatting about my job with anyone else. I am aware (from observation) that other startup founders talk about their companies endlessly, to the peril of all social gatherings. Not me, not ever.

All the companies I’ve started have been successful by objective standards but that doesn’t mean I am inclined to brag. Hubris is both dangerous and idiotic. It is a simple fact that the majority of startups fail, which isn’t surprising. Does the world need another social media company? Digital marketing and real estate innovations? Companies claiming to be tech because they sell stuff online? Blockchain? And don’t forget scooters!

What I would ask is: are any of these ideas… necessary? Maybe. I don’t know, but I’m also not very interested. Yes, people sometimes make a lot of money working in startups, but it is more common to lose both money and time. I hate wasting money, and I’ve been living on borrowed time since 1983.

As a general rule I think the startup scene is bloated with bad ideas and irrational investments. I also believe that the amount of VC floating around is distorting traditional economic indicators. High consumer debt, cuts to infrastructure investment, and the fragility of the international supply chain are additional troubling factors. We’re in another bubble, if we’re lucky, but it is far more likely we’re riding unicorns toward economic armageddon.

This analysis didn’t deter me from starting a company, but it did make me cautious about which sector to operate in. I thought about it for a good long time before assembling a team of super smart people, who are working on products to address fundamental software security issues. We had customers before we had a prototype.

This is a very old-fashioned way to run a tech company, and the opposite of current received wisdom. If anyone corners me and asks for my advice, this is what I say: trouble is coming, and we all need to be prepared.

07.02.19 outlandish

When I was born my parents were teenagers, and functionally homeless. They felt lucky when they were allocated public housing in a dire and crime riddled cluster of shacks near Oyster Bay. My mother believed that ratty little duplex was key to improving their situation; it was easier to get and keep jobs once they had a place to live. From that base, they spent the next several decades working tirelessly to improve our material circumstances.

My mother enrolled me in Head Start as soon as I qualified, and compelled me to go even though I found the other children terrifying. Because she needed the free hours in her day, but for deeper reasons: she credited that program with giving me the skills I needed to be successful. Before she died I suggested that having a good mother was more important, but she disagreed. From her perspective, free basic preschool was the single factor that prepared me for anything life would bring.

When I was six our family entered a government cooperative program for low income families to build their own houses. We spent a year framing, hammering, pouring concrete, literally building a neighborhood. Sure the houses were built on wasteland, and the single shared well was often contaminated, but the houses belonged to us. And there was another bonus – the new neighborhood was on the other side of the county from our family. I started kindergarten fresh, without the reputation that followed her maiden name.

The other miraculous change that year: my mother got a full-time job in the naval shipyard, doing classified work she wasn’t allowed to talk about. Her earnings would have provided a reasonable standard of living, if I had been healthy. But I was diagnosed with terminal cancer, and she found herself in an impossible situation, because her job provided the health insurance that saved me. The bills were punishing, we were constantly on the brink of bankruptcy, and she could not take time off work to care for her sick child. I was sent to school while literally radioactive because there was nowhere else to go.

But she kept the job, and she kept our family together, and I survived. It took a couple of decades to pay off the medical debts, and the job at the shipyard was the source of that money. That is where she remained until just before her death at age 63. Her job with the Department of Defense held our little family to a high standard of conduct (unlike the criminal branches of the clan), and she set the example of how people are supposed to exist in the world. She served her country, and her family, and she expected others to do the same. When anyone complained about normal things, or even tragic things, her most common reply was boo-fucking-hoo.

From the first day of kindergarten until I graduated high school, my parents did not attend any school events. They did not meet with teachers, and they certainly did not intercede on my behalf in the long battle I waged to gain access to mainstream assimilated education. By age thirteen I knew all about Section 504, by age fifteen I had threatened lawsuits often enough I was catapulted out of remedial programs and into honors classes. My mother thought the fight was good for me. She reckoned life is hard, then you die.

What she hadn’t bet on was the fact that her efforts would encourage me to go even further. Free public education was considered good, but it was supposed to end at 18, when a smart kid could hope for a job in the shipyard or on the ferries. There was no reason to think I had any other prospects, since I too had become a functionally homeless teen parent.

It was a shock to the family that I wanted to go to college; when I finished my undergraduate degree in two years and enrolled in grad school my actions were disruptive, abhorrent, unforgivable. The choice certainly killed my marriage, and also created a terrible rift in my relationship with my mother. She didn’t like airs and graces, or fifty cent words when a nickel would do.

When I landed my first job in government I believed I was following her example, protecting my child, serving my community. But my education and litigious nature made me that worst of all things: management. And I did it without getting my hands dirty, or putting in the hours. It was insulting that I was a boss at age 22, when nobody in any generation of her family ever achieved that — or indeed wanted to. Management is the enemy, not your kin.

My relationship with this status is likewise problematic. I’m a working class woman in every particular, regardless of title or rank, and I make no effort to mask my antecedents. I don’t aspire to be middle class or even to understand what middle class people care about. They annoy me, middle class humans, with their smug assumptions and comfortable lives.

When my mother made sharp comments about my failures as a daughter I shrugged and told her it was her own fault – she set the standard, I’m just trying to live up to the example. The importance of family, service, and stability are the values she instilled. I’ve never found a better belief system.

But then my children grew up and shocked me, the way I shocked my own mother. Because my kids, though born into poverty, had a softer version, defined by a mother with an advanced education and professional aspirations. They didn’t know they were poor, because I made up elaborate games to distract them and keep them busy, and because they hardly ever went to school, and because we moved constantly.

I grew up near the town my immigrant ancestors settled in the 1890’s. The regional library was an hour away, if I could get a ride, and there was a strict limit on how many books you could borrow. Our extended family of junkies and felons were always around, demanding cash and rides and attention. School was the place I felt safe, where I could read and dream, and I resented the unnecessary (and unlawful) obstacles that were placed in my way by teachers more concerned with absences than aptitude.

In contrast, my kids traveled the world, living for long stretches in hotels in Europe, corporate housing on the west coast, the faculty club at Berkeley, student housing at CMU, in genteel squalor in Cambridge, in a cottage on the grounds of an ancient college in Oxford. We didn’t have enough money for basic things like food and clothes — but we had libraries, and museums, and parks, and countless visiting scholars arguing over the dinner table. We had careers instead of jobs.

My kids went to school largely when they could organize it themselves, which was only intermittently. The younger child did finish primary school, but the elder attended classes for perhaps two years (cumulatively) before age eighteen. My opposition to standardized childhood education is absolute: I think it was principally devised to create conformity and clerks. Good luck to anyone who tried to make my offspring normal, or make them do anything. I didn’t let them have personal computers, television, or video games — but other than that made no effort to interfere. They were not homeschooled. They just did, well, whatever.

But to me, higher education is an entirely different matter. And it is in fact possible to go to university without any preliminary work, if you are smart and work hard. I inflict this notion on everyone in my vicinity, proselytizing against K-12 and in favor of college at every opportunity. I find the weird kids and the dropouts and offer to teach them my tricks. I locate the ones who think they need permission, and spell it out.

Mostly though I debunk cultural assumptions. Not good at math? Doesn’t matter – look at my mathematician husband, a junior high dropout who never studied the subject before grad school. Family doesn’t support you? Gotta support yourself. Impostor syndrome? Easy: I agree, you’re an impostor. Fake it til you make it.

I’ve devoted hundreds of hours to helping people figure out applications, scholarships, strategy. I take them on tours, and write their recommendation letters, and provide encouragement that is perhaps at times a little too intense. If the subject of education comes up at one of my dinner parties, regular guests see my mouth open and chant Have you considered grad school?

My own kids didn’t really have a choice; their scary working class immigrant mother accepted nothing else. I had to make my own way in life and they were going to do the same whether they liked it or not. At age 18 they were either out of the house, or they were in school. If they could figure out how to support themselves, fine. If not, too bad.

Both tested my tolerance – one with serious illness (childhood cancer rendered me deeply unsympathetic to anything short of death) and one with standard doldrums (when that one turned 18 without a plan I moved to another country the very next day, leaving them behind to sort out finances the hard way – true story). No exceptions, no excuses.

They didn’t particularly want to go to university but did the calculations, failed to find jobs, and accepted their fate. I nudged, debated, and basically harassed my teenagers to apply broadly, accept the best offers, and start proper degree programs.

Imagine my surprise when the eccentric little unschooled cygnets proved to be excellent, disciplined, self-directed students. Now imagine the sheer terror I felt when I realized they were not interested in practical things like computer science or contract law. Oh no – they wanted to study anthropology and art and music.

When I was young I thought my mother wasn’t proud of me, because her reaction to my accomplishments registered as baffled. Now I look at my own children and understand how she felt.

My eldest is finishing her PhD, my youngest has a fistful of grad school offers from prestigious institutions. He is going to study opera, of all the outlandish things. I’m proud of them, but also perplexed.

How did this happen? How did I stop a cycle of poverty, abuse, and exploitation stretching back generations? How did I produce children with the intelligence and grit required to achieve at such high levels?

The answer is: I didn’t do much except survive. The real work was done by my mother, who put me in Head Start, and built a house with her own hands, and got a job at the shipyard, and never let me repay the debt caused by my cancer.

Her sacrifices are astonishing, and her presence is missed. If she were here we could sit at the kitchen table eating coffee cake and marveling over my odd children, and all the strange things they will do with their lives.

journal

- January 2020

- December 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- July 2013

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003